Studio Ghibli is home to some of the greatest animators in the world, but outside Japan, its catalog has tended to be either difficult to find or the purview of pricey collector’s edition discs. Thankfully, that changed when Netflix (in the UK) and Max (in the US) snapped up streaming rights. Now, although a few curiosities escape Western availability—such as Whisper of the Heart spinoff Iblard Jikan—almost everything from the studio is available at a click.

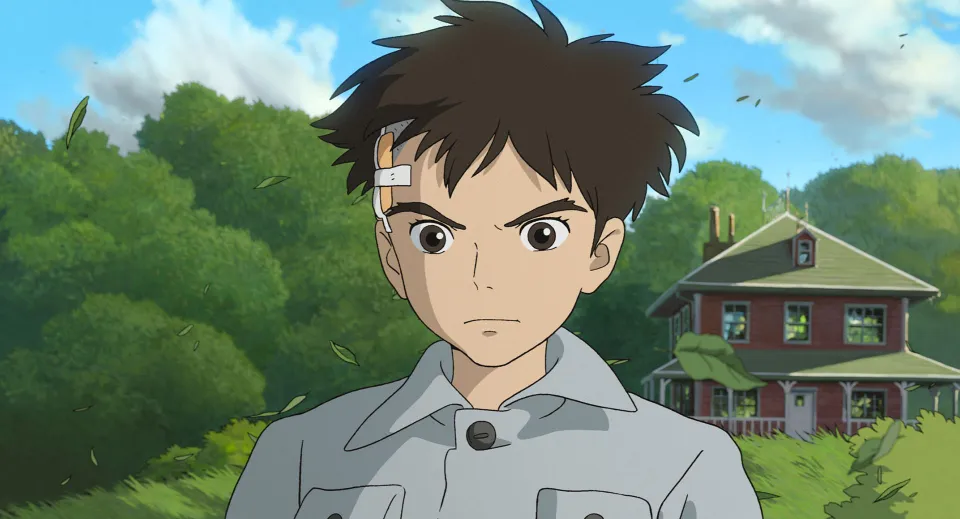

Now, with visionary director Hayao Miyazaki’s final film, The Boy and the Heron, currently making its way to international cinema screens, it’s time to reevaluate everything that came before. This is the definitive ranking of the rest of the legendary animation house’s library, and where to find them.

24. Earwig and the Witch

You can almost imagine the cold, calculated decisionmaking that went into Earwig and the Witch. After all, Diana Wynne Jones’ Howl’s Moving Castle became one of Studio Ghibli’s most beloved films, so surely adapting another of the author’s books was a smart idea—and with this one following an orphaned girl adopted by a witch and forced into servitude, it probably seemed a perfect blend of Howl’s, Kiki’s Delivery Service, and Spirited Away. Plus, CGI animated films by Disney and Pixar regularly dominate the box office, so what could go wrong with adopting the style? A lot, it turns out—Goro Miyazaki’s attempt to deliver Ghibli’s first 3DCG feature is a bland, lifeless affair that, despite the leap into the third dimension, looks flatter and duller than anything else the studio has released. Beyond the lackluster visuals, the movie is a narrative disappointment too, with an extended middle act that never matures into a finale, leaving backstories, relationships, and questions unresolved by the time the credits roll. Studio Ghibli’s worst creative failure.

23. Tales From Earthsea

Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea is one of the finest fantasy sagas in literature, but has been blighted with terrible adaptations in other media. Sadly, even Studio Ghibli’s brand of magic couldn’t break that curse. The film’s bizarre development cycle didn’t help—Hayao Miyazaki had sought the Earthsea rights for years, but was busy directing Howl’s Moving Castle by the time Le Guin gave her approval, leading Studio Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki to tap Hayao’s son Goro (originally a landscape architect) to direct. The elder Miyazaki disapproved, given his son’s inexperience, and was proven right. This Earthsea is a mess, an incoherent jumbling of scenes and characters from Le Guin’s work, resulting in a generic fantasy with no real narrative thread and barely any of the visual beauty of the studio’s other works. On the film’s release, Le Guin would say to Goro: “It is not my book. It is your movie. It is a good movie,” though later was far harsher, criticizing the film’s violence.

22. Ocean Waves

1993’s Ocean Waves was essentially a training exercise for Studio Ghibli’s younger creators, a made-for-TV film helmed by outsider director Tomomi Mochizuki. It’s also a contender for the studio’s most realistic and grounded work, forgoing Ghibli’s penchant for the fantastic in favor of a poignant story of teen friendships, fractured families, and the pains of adolescence. Despite this, it’s also quietly charming, perfectly capturing the beauty to be found in everyday life. The film follows the increasingly strained relationships between Rikako, who resents being shipped off from bustling Tokyo to the much smaller city of Kōchi following her parents’ divorce, and her new classmates, well-meaning but academically struggling Taku and class leader Yutaka. There are plenty of lingering looks and wistful staring into middle distance as the young cast navigate their feelings and futures, making for a mood that’s constantly caught between melancholy and contemplation, but at only 72 minutes, it doesn’t outstay its welcome. It’ll be too slow for some, but anyone open to a serious animated drama will be well served.

21. From Up on Poppy Hill

A collaboration between both Miyazakis, with Goro directing from a screenplay by Hayao, results in the former’s best feature work to date. Set in 1963 Yokohama, From Up on Poppy Hill follows Umi, who lives in a boarding house while her mother studies in the US, and Shun, a member of their school’s newspaper team, as they fight to save a clubhouse from demolition. Yet as the pair grow closer, they learn that they may share more than a cause: With records a mess following World War II and the Korean War, an old photo points to them sharing a father, too. While it’s slow to the point of ponderousness at points, Poppy Hill still delivers some stand-out moments of animated beauty, and its youthful, optimistic leads are a real delight.

20. My Neighbors the Yamadas

An adaptation of a newspaper comic strip, My Neighbors the Yamadas is a candidate for Ghibli’s most experimental movie. Not only did director Isao Takahata eschew cel animation to create the studio’s first digital production, but it’s questionable whether it’s a “movie” by any traditional definition. There’s no real through-line, instead presenting viewers with a series of vignettes focused on the Yamada family as they navigate the quirks and eccentricities of daily life. The tone can vary wildly from short to short—silly enough to place the Yamadas in the folk story The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (the same story that would later inspire Takahata’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya) at one moment, but grounded enough to explore major familial conflicts (like control of the TV remote) in the next—but with its living watercolor visuals and a beautiful score by Akiko Yano, Yamadas is never less than utterly joyful.

19. The Cat Returns

The Cat Returns follows a girl named Haru, who finds herself betrothed to the Prince of Cats following an act of kindness. Drawn into the Cat Kingdom and slowly changing into feline form, her only hope is the gentlemanly Baron, the humanoid cat from Whisper of the Heart. Director Hiroyuki Morita’s fantasy sits somewhere between spinoff and sequel to that film—or, at least, to the fantastic asides within it—which makes this less of a standalone effort than most of Studio Ghibli’s works, but it’s still a visual feast packed with charming characters and gleeful weirdness. At only 75 minutes, it’s a nice, breezy watch, too.

18. Ponyo

Hayao Miyazaki’s take on The Little Mermaid could have been great, especially if some of the darker elements of the original story survived the transition. Instead, Ponyo feels more inspired by the already sanitized Disney version and made even more kid-friendly here (a theme song with the lyrics “Ponyo, Ponyo, fishy in the sea” doesn’t help). Ponyo is the daughter of a sea wizard, separated from her family and rescued by Sōsuke, a 5-year-old boy with whom she decides she wants to stay. The romance element of the source material obviously doesn’t work with such young protagonists, and the progression of the story is far simpler and blunter than audiences may expect from a Ghibli work. Still, it packs in the magnificent animation quality that the studio built its reputation on. Ponyo is Miyazaki’s weakest film—but the weakest work by a master of his craft is still worth a watch.

17. Only Yesterday

This might be Studio Ghibli’s most controversial release, a movie barred from release in North America for a quarter-century due to its shocking content. The content in question? An incredibly mild, non-graphic flashback scene where protagonist Taeko has her first period. This everyday biological reality was too extreme for distributor Disney, and Only Yesterday became the domain of bootlegs and imports for years. Thankfully, this quiet, contemplative piece from director Isao Takahata is now readily available, and Taeko’s journey back to her rural home village to escape city life, reflect on her childhood, and decide what she wants out of life can be easily enjoyed. A sedate film—and, like many of Ghibli’s dramas, likely to be too slow for some—but it stands as a beautiful piece of animated filmmaking.

16. When Marnie Was There

A subtle, rewarding story about adolescence and identity based on a 1967 novel of the same name by British author Joan G. Robinson, When Marnie Was There follows Anna, a shy and withdrawn girl who struggles to connect to anyone. As she moves to a seaside town to recuperate from chronic asthma, she meets Marnie, a mysterious girl who lives in a secluded mansion accessible only by rowboat—and who insists that Anna keeps their growing friendship secret. The story straddles the line between Ghibli’s dramas and fantasies, with only very gentle supernatural themes, but it’s the beautiful locations, gorgeous animation, and heartfelt connection between its protagonists that make it stand out. The second and last of Hiromasa Yonebayashi’s films at Studio Ghibli, When Marnie Was There showed the director was one to watch.

15. The Red Turtle

One of Studio Ghibli’s strangest offerings, The Red Turtle is a dialog-free survival epic/mythical romance. A shipwrecked man finds himself alone on an island, prevented from leaving by the titular red turtle—until the creature reveals itself to be something else entirely, and the man’s life changes forever. The film’s mixed heritage—a collaboration between Ghibli and several European arts and media companies, and directed by Academy Award–winning Dutch animator Michaël Dudok de Wit—makes it one of Ghibli’s most visually distinctive films, with a blend of influences including Franco-Belgian bandes dessinée giving it something of a Tintin flair at times. Dreamlike and almost meditative, The Red Turtle is perhaps the most unique film in the studio’s library.

14. The Secret World of Arrietty

One of Studio Ghibli’s greatest talents is being able to show the sheer wonder that can be found in the world around us, and Arrietty is one of the best examples of this. Transplanting Mary Norton’s classic novel The Borrowers to Japan, the film follows the young boy Shō as he befriends the eponymous Arrietty, one of the “little people” who live in the hidden spaces within his aunt’s house. Hiromasa Yonebayashi’s directorial debut, Arrietty’s sumptuous visuals reveal the magic in everything full-grown humans overlook. Oddly, there’s a UK and US dub of the film with different casts, but the UK one featuring Saoirse Ronan, Tom Holland, and Olivia Colman is the one to go for, especially as the US version needlessly tweaks the ending with some additional lines not found in the original production.

13. The Wind Rises

Hayao Miyazaki’s previous “final film” before The Boy and the Heron—never has a man been so pathologically incapable of retiring—The Wind Rises adapts his own manga of the same name into a stunningly animated pseudo-biography of Jiro Horikoshi, the chief engineer behind some of Japan’s key aircraft during World War II, notably the Mitsubishi A6M Zero. This is no propaganda piece though, as Miyazaki delivers an honest exploration of 1930s Japan, a country wracked by recession and disease, alongside a meticulous depiction of how planes are designed and constructed. His portrayal of Horikoshi is slightly fictionalized—the real-life figure had an older brother, not a younger sister, as here—but is a likable, optimistic figure who was almost possessed by his dreams of flight, despite fears of how his designs may be used. A thoughtful retrospective inspired by his own love of aviation, The Wind Rises is one of Miyazaki’s most personal movies.

12. Whisper of the Heart

Based on a manga by Aoi Hiiragi, Whisper of the Heart blends coming-of-age drama with a tale of fluttering first love. It tells the story of Shizuku, a 14-year-old girl who aspires to be a writer, and Seiji, a boy who aims to make the finest violins in the world. Yet while the personal drama is front and center, there are also some breathtakingly beautiful fantasy sequences, bringing to life the story Shizuku invents for The Baron (an antique cat statue, who would later feature in The Cat Returns). It’s these sections, set in a surreal world of floating islands drawing on the impressionistic artwork of Naohisa Inoue, that elevate the movie as a whole—well, those, and a very creative reworking of the song “Take Me Home, Country Roads” that’s surprisingly central to the plot. The sole feature directed by Yoshifumi Kondō, a veteran animation director and planned successor to Miyazaki and Takahata who tragically died just a few years after the film’s release, Whisper of the Heart endures as a landmark work from a talented creator.

11. Porco Rosso

Imagine Indiana Jones as a pilot instead of an archaeologist… and with his head transformed into a pig’s. That’s the basic gist of Porco Rosso, Hayao Miyazaki’s greatest film about flying and an underrated classic. Set in 1930s Italy, Porco Rosso, the Crimson Pig, is a hotshot pilot caught up in a rivalry with sky pirate Curtis, competing for both aerial supremacy and the love of Gina, a cabaret singer and hotel owner. The film is deliciously indulgent on Miyazaki’s part, a way to showcase his love of vintage planes, but is packed with thrilling chases, shoot-outs, and high-stakes fist fights, making it a classic adventure film. Plus, it gave the world the immortal line “I’d rather be a pig than a fascist.” Perfect Saturday afternoon viewing.

10. The Tale of the Princess Kaguya

Isao Takahata’s final film is a stunning achievement, adapting a thousand-year-old fable into a modern masterpiece. Found as a baby inside a bamboo shoot, young Kaguya brings joy to her adoptive parents. Hailing from the moon, Kaguya relishes the simple pleasures of her bucolic life, until the very people who banished her to Earth demand she return and Kaguya faces losing everything and everyone she loves. The visuals are unlike anything else, all dreamlike watercolors and half-remembered sketch lines flooding into each other to create exquisite forms of movement, while Joe Hisaishi’s score is one of the finest to grace a Ghibli film. Once the most expensive Japanese film ever made—a record supplanted by The Boy and the Heron—The Tale of the Princess Kaguya is also an almost-overwhelmingly emotional affair. Watch with people you don’t mind seeing you weep uncontrollably.

9. Kiki’s Delivery Service

Young witch Kiki has just turned 13 and, according to custom, must continue her magic training by living alone for a year. Having only mastered flying on her broomstick, Kiki and her talking cat, Jiji, travel to the port city of Koriko, where she sets about helping the locals as a speedy delivery girl. And … that’s it. The closest thing to a central plot is Kiki’s growing friendship with Tombo, a boy obsessed with flight (often suspected of being a cheeky bit of self-insert on director Hayao Miyzaki’s part, given his own well-documented love of aviation), but ultimately Kiki’s Delivery Service is an energetic coming-of-age story, an almost episodic collection of the well-meaning hero’s small adventures. That simplicity is part of its mountainous charm though, crafting a mood more than a story, one of finding your confidence, embracing adventure, and meeting the world with hope and optimism. An enduring classic, whatever your age.

8. Pom Poko

Tragically, Pom Poko is perhaps better known as “the one with the raccoon balls,” and that’s just wrong. For one, the protagonists aren’t raccoons at all, but rather tanuki, playful creatures known in Japanese folklore for trickery and shapeshifting. For another, tanuki anatomy’s reputation for magical properties colors what is one of Isao Takahata’s greatest works, an environmental parable that explores the impact of humanity’s urban sprawl on forest habitats and the creatures that inhabit them. It’s a whimsical approach to surprisingly heavy material, and for every fanciful battle between warring tribes of tanuki, there’s a heartbreaking moment showing the real cost to the natural world of our relentless modernization. Quirky but somber, Pom Poko’s messages will hang with you long after you finish watching.

7. Howl’s Moving Castle

The first of Diana Wynne Jones’ novels adapted by Studio Ghibli (and far more successfully so than Earwig and the Witch), Howl’s Moving Castle allowed Hayao Miyazaki to present his most overtly anti-war statement to audiences. Set in a quasi-realistic world where a conflict rages with a mixture of magic and military might, the film focuses on Sophie, a young milliner aged into a withered crone by a curse from the Witch of the Waste. In search of a cure, she encounters the eponymous castle—a daunting construct meandering impossibly through the countryside—and its vainglorious owner, the wizard Howl. While Howl’s powers are sought by both sides to try to turn the tide of the increasingly devastating war, it’s the focus on Sophie and her relationship with Howl and Calcifer, the fire spirit who powers the castle, that really allows Miyazaki to emphasize the impact of war at an individual level. It’s all let down slightly by a sloppy, rushed ending, but the film’s mixture of charming characters and sumptuous animation is classic Ghibli.

6. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Although technically not a Studio Ghibli film—released in 1984, its success laid the financial groundwork for Miyazaki, Takahata, and producer Toshio Suzuki to found Studio Ghibli in June 1985—Nausicaä is synonymous with the studio. For good reason, too: Miyazaki’s postapocalyptic fantasy, adapted from his own manga, proved a pivotal moment in animation history. Set 1,000 years after a civilization-ending war known to the survivors’ descendants as the Seven Days of Fire, its tale of the titular princess trying to save her people from ecological catastrophe is brought to life through groundbreaking work from future titans of the medium (a particularly notable sequence is helmed by Evangelion creator Hideaki Anno). Filled with what would become hallmarks of both Ghibli and Miyazaki’s output—heroic young women, the joy of flight, and the delicate state of the natural world—Nausicaä set the standard for everything that followed.

5. Grave of the Fireflies

Warning: There’s a fair chance this film will traumatize you. Isao Takahata’s magnum opus follows siblings Seita and Setsuko as they struggle to survive in the wake of the 1945 fire bombing of Kobe, and Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II. Orphaned by their parents and abused by surviving extended family, they try to eke out an existence in the wastelands that were once their hometown, only to face starvation and disease. It is a bleak and harrowing work, and unapologetically so, painted in sorrowful, mournful tones throughout, a film about a world lost, of innocence lost, of pain and suffering, of the cost of war on the most innocent, but also of enduring love. Licensing peculiarities related to the original short story by Akiyuki Nosaka mean it’s one of the few Studio Ghibli films not available on Netflix (UK) or Max (US), but it’s available to buy or rent digitally in both territories, and has a rather excellent Blu-ray release for physical media aficionados.

4. Laputa: Castle in the Sky

The first official Ghibli film, 1986’s Laputa: Castle in the Sky is a distillation of everything that would make the Studio great, both onscreen and behind the scenes. Written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, produced by Isao Takahata, and with a phenomenal score by Joe Hisaishi, it’s a showcase of the greatest talents at the beloved animation house, while the action-adventure story is as rousing as Ghibli gets. When Pazu, a young miner, rescues Sheeta, a girl who falls from the sky, it leads them in search of a castle hidden behind the clouds, a quest that brings them into conflict with shady government forces, sky pirates in steampunk airships, and devastatingly powerful robots created by an ancient civilization. Inspired by influences as varied as Gulliver’s Travels and Miyazaki’s trip to Welsh mining towns, Castle in the Sky is Ghibli’s first masterpiece.

3. Spirited Away

Steeped in a mixture of Shinto and Buddhist lore, Spirited Away is a mesmerizing affair, and one that firmly established Studio Ghibli’s reputation outside of Japan (winning the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature will do that). When Chihiro steps into a fantastic world populated by gods and monsters, she loses everything—even her name. Renamed Sen by the witch Yubaba and forced to work in a bathhouse for yōkai and spirits, her struggle to return to the world she knew takes her on a tour of an unimaginably beautiful spirit world, filled with unforgettable figures all brought to life with director Hayao Miyazaki’s inestimable attention to detail. Comparisons can be drawn to Alice in Wonderland or The Wizard of Oz, but this is pure Ghibli magic.

2. Princess Mononoke

While Spirited Away won Miyazaki the Oscar, there’s a strong case to be made that Princess Mononoke is the film that should have won it. Set in a version of 13th-century Japan, the animated epic depicts the struggle between the animal gods who protect the forest and the humans who want to cut it down to mine iron. On one side is San, a young woman raised by wolf gods, who despises humanity. On the other is the complex Lady Eboshi, a genuine humanitarian and feminist building a home for those discarded by wider society, but whose hubris precipitates chaos and destruction. Caught in the middle is Ashitaka, a prince blighted by a demon’s curse, whose search for a cure leads him to try to reconcile both factions. It’s a richer, more complex tale than almost anything else in Ghibli’s oeuvre, wrapped in narrative shades of gray even as its visuals paint a lush, vivid world of savage beasts and inquisitive spirits. The balance between humans, technology, and nature is one of Miyazaki’s favorite themes, and Princess Monokoke is the most evocative portrayal of his convictions.

1. My Neighbor Totoro

Of course My Neighbor Totoro tops this list—the legendary creature became the Studio Ghibli’s mascot for a reason. When Mei and Satsuki move with their father to an old house near the hospital where their mother is recuperating from a long-term illness, they stumble upon a world of mysterious nature spirits unseen by adults, led by the gentle giant Totoro. Like Kiki’s Delivery Service, Totoro is a series of gentle, beautiful adventures as the girls bond with the mysterious creature, but it holds together better thanks to the emotional weight behind the girls’ circumstances. The film also marks the first appearance of so many Studio Ghibli staples—notably susuwatari, the adorable soot sprites that crop up in several other movies—and is absolutely crammed with iconic imagery and standout moments. The bus-stop shot with Totoro and the girls standing in the pouring rain, the Catbus racing through fields, Totoro’s bellowing roar echoing over the countryside—it’s all so memorable. Not just a great film for kids, but one of the great films about the magic and wonder of being a kid. Watch it, then watch it again.